To Benjamin Apthorp Gould Fuller

To Benjamin Apthorp Gould Fuller

22 Beaumont St. Oxford

Sunninghill, Berk, England. September 10, 1918

It is a real pleasure to hear from you. I knew that you were in France officiating in some useful capacity, but had no definite address. Some six months ago I sent a pamphlet to you at Sherborn but I daresay it never reached you. The Harvard world seems far away and not very enticing: Heraclitus was right, I think, in believing that Dike presides over the lapse of things, and that when they pass away, it is high time they should do so. If you go round the world after the war, I hope it will not be at a hurried or an even pace, and that you will spend three quarters of the time of your journey in the places which after all are most interesting and where there is most (for us, at least) to discover—in western Europe. Then I shall hope to come across your path and perhaps even to make some excursion in your good company: this long confinement in England; though pleasant in itself, is beginning to grow oppressive, and I often think with envy of those in Paris or beyond. At the same time, I hate to face suspicious officials, and any unusual difficulties and complications in the machinery of travel; so I have remained in my Oxford headquarters now for three years, and expect not to abandon them until the war ends.

. . .

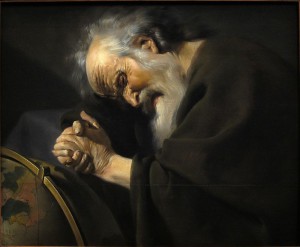

My good friend Strong has had a bad time—laid up with a paralysis of the legs—and is still hardly able to walk. The attack fortunately came on when he was at Val Mont above the lake of Geneva, a place he likes and where the doctors inspire him with confidence. He hopes soon to return to Fiesole: meantime I have been separated from him and have missed him, for in his quiet dull way he is the best of friends and the soundest of philosophers—good ballast for my cockleshell. . . . I am . . . deep in a book to be called Dominations & Powers,–a sort of psychology of politics and attempt to explain how it happens that governments and religions, with so little to recommend them, secure such a measure of popular allegiance. Of course, behind all this, is the shadow of the Realms of Being, still (I am sorry to say) rather nebulous, although the cloud of manuscript is already ponderous and charged with some electricity in the potential state. I don’t know if any lightning or thunder will ever reach mortals from it.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Two, 1910-1920. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge MA