To José Sastre González

To José Sastre González

Via S. Stefano Rotondo, 6

Rome. August 13, 1943

Querido Pepe,

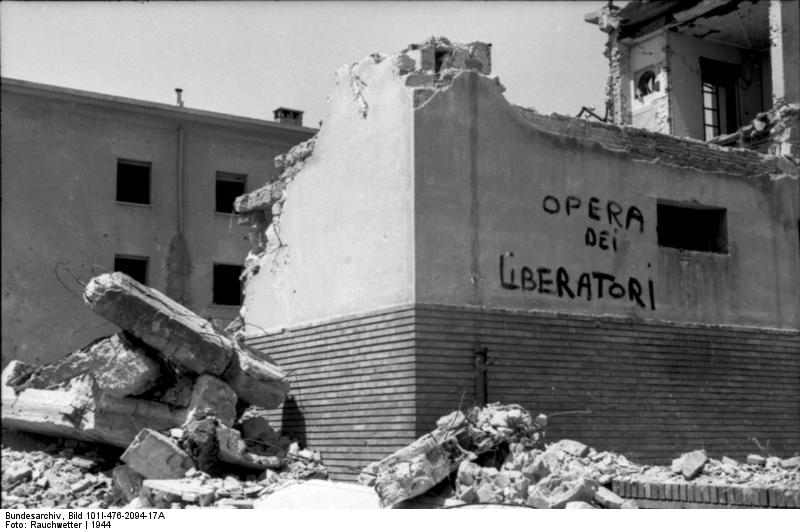

Hoy, dia del segundo bombardeo de Roma, recibo tu carta del 25 de Julio. Comprendo que penseis en “los malos ratos” que habré yo pasado aqui, pero no, yo sigo sin novedad y tranquilo, sin cambiar en nada la rutina del dia. Hay que darse cuenta de que vivo en un convento que es a la vez hospital. Todo está en regla, y si ocurriera alguna desgracia en esta casa, no podia el auxilio estar mas a mano. Este barrio no es ni céntrico ni industrial, en gran parte compuesto de jardines, al mediodía del Coliseo y del Laterano. Si cayera alguna bomba por aquí seria por casualidad, y yo confio en que saldremos ilesos de la guerra.

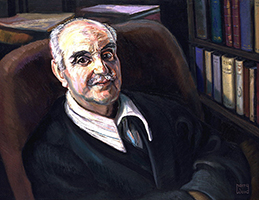

Naturalmente, el ánimo sufre de oir hablar de tantos horrores, pero a mis años, conociendo que soy inútil, yo me consuelo con mis libros y mi filosofía, como si se tratase de la historia antigua. Además, todo lo que ahora ocurre en el mundo es impresionante. Muchas veces recuerdo las ideas de mi padre, y me figuro lo que él hubiera dicho de todo esto.

No hay que pensar en viajes. Eso me agitaría mucho mas que el ruido de las bombas, o de la artillería contra-aerea, que es la que mas hiere los oidos.

De salud, bien, y con esperanzas de llegar a ver como ternina esta tragedia.

A ti y a toda la familia un apretado abrazo de tu tio,

Jorge

Translation:

Dear Pepe,

Today, on the day of the second bombing of Rome, I have received your letter of July 25. I understand why you think about “the difficult moments” that I must have had here, but I have nothing new to report and am calm, without changing in any way my daily routine. You must realize that I live in a convent which is at the same time a hospital. Everything is in order, and if any misfortune should strike this house, help could not be closer. This area of the city is neither downtown nor full of industry; it is made up in large part of gardens to the south of the Colosseum and the Lateran. If a bomb should fall here it would be by chance and I do believe that we will come out of the war unharmed.

Naturally the mind suffers when it hears talk of so many horrors, but at my age, knowing that I am useless, I find solace in my books and my philosophy, as though it were a matter of ancient history. Besides, everything that is happening in the world is out of the ordinary. I often remember my father’s ideas and imagine what he would have said about all of this.

You mustn’t think about trips. That would upset me much more than the noise of the bombs, or of the anti-aircraft artillery, which is the one that hurts the ears most.

As far as health goes, I am well and I have hopes of living long enough to see how this tragedy ends.

For you and the whole family a strong embrace from your uncle,

Jorge

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Seven, 1941-1947. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2006.

Location of manuscript: Collection of Sra. Eduardo Sastre Martín, Madrid, Spain.

To Richard Colton Lyon

To Richard Colton Lyon