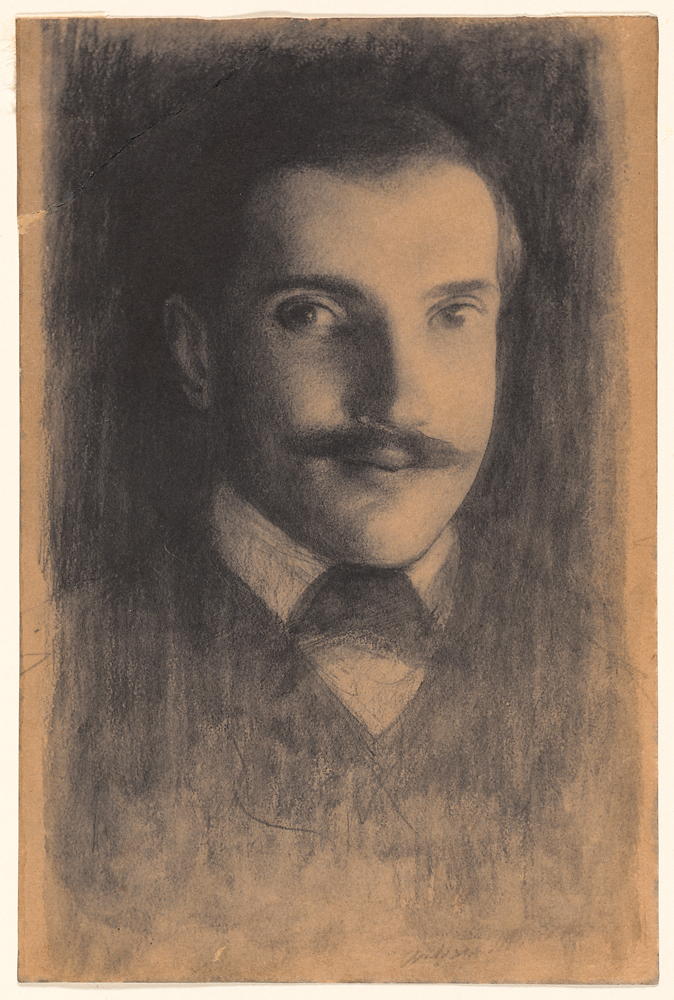

To Charles Augustus Strong

To Charles Augustus Strong

Hotel Cristallo

Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy. July 25, 1926

Dear Strong,

I have just finished “Sous le Soleil de Satan”. Is the author a young man? If so, I think he may do very good things. I like his ideas (when they are ideas) and his prejudices: the portrait of Anatole France at the end is excellent. So the other minor characters: even the Devil is plausible, if you fall back on mediaeval ways of conceiving him. But there is a lot of rant and confusion: I had some difficulty in following the thread of events or emotions in places, and felt like skipping, or dropping the book altogether. Neither the hero nor the heroine is intelligible. It looks as if the author himself didn’t know exactly what was up. That the world is given over to the devil and that there are shady sides and bitter dregs in every life is perfectly true: but we must distinguish the part which is inseparable from existence of any sort—from flux and finitude—in this evil, and the part that is remediable. No doubt a very exacting spirit might rebel against existence itself: but I don’t know what he could find to substitute for it. Certainly this book suggests nothing: it does not represent religion as offering any real refuge: even there all seems to be weeping and gnashing of teeth. Why so tense, little Sir?

The Drakes are gone after staying five days—I am writing an article about Platonism and “Spiritual religion” apropos of a book of Dean Inge’s on that subject. It is an interruption, but I have definitely dropped the reins on the neck of my weary old Pegasus, and am letting him amble as he will. I shouldn’t accomplish any thing better by applying the bit and spurs.

And you?

Yours ever, G.S.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Three, 1921-1927. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2002.

Location of manuscript: Rockefeller Archive Center, Sleepy Hollow NY