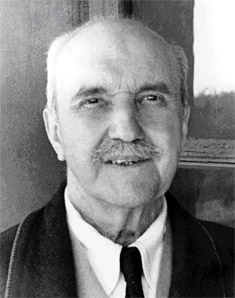

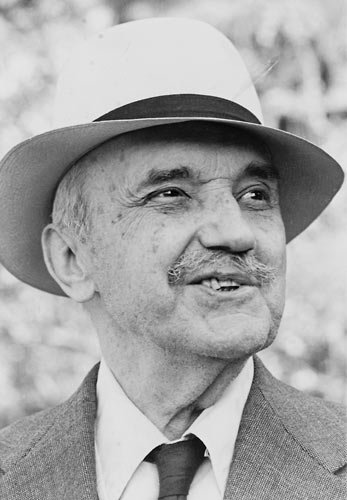

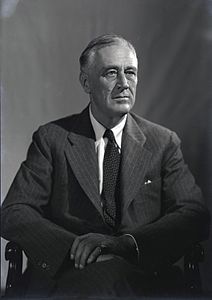

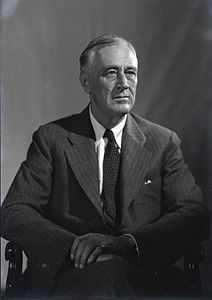

To Daniel MacGhie Cory

To Daniel MacGhie Cory

Hotel Miramonti

Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy. July 14, 1933

This veiled threat of discontinuing your allowance is not new on S.’s part: he has spoken to me in the same sense repeatedly; and the collapse of the dollar, added to a great fall in capital, will reduce his income, in Italian money, to perhaps half what it was. As he can’t very well give up his villa or motor, or take in boarders, he may be really compelled to dismiss you with his blessing. When he has talked of leaving you (for your own good, of course) to make your way in the world, I have always said that perhaps it might really be for your ultimate interest. I feel partly responsible for having kept you so long dangling, and I should do what I could to help you in any difficulty. After all, how long are S. and I likely to live? The important point for you is that he shouldn’t revoke the legacy in which you are concerned. There is a trick about it, even as it stands; but with the old value of the dollar it would probably and ultimately have provided you with an income sufficient for all your needs, especially if you remained unmarried. But if the dollar settles down to be half a dollar, or 66 cents, that prospect becomes less smiling. Still, that is the point that really matters: and I have besought S. not to rescind his arrangements in that particular: and when he last spoke to me about it, perhaps a year ago, he seemed definitely determined not to make any change. In order to keep him in this mood, it is in your interest to continue doing what you can to keep his conscience satisfied. You know his character as well as I do: in fact, better, perhaps; because until lately I took him so completely as a matter of course, and as a . . . thoroughly conscientious and just man, that I may not have seen to the bottom of the well. His attachments are not matters of personal affection . . . He has moments in which he is enthusiastic about you: but it is because he then imagines that you will fit in beautifully into his plan of work. He has never cared for anything but for his work, his health, and his duty: his health, because necessary to his work, and his work, perhaps, because necessary to make it an absolute duty to nurse his health. He loves you, he loves us all, when, and in so far as, we fall into this picture: otherwise he feels no bond. You are therefore always in real danger of being erased from the tables of the truly deserving.

My nephew wrote the other day, saying that my income for the halfyear ending on the first of this month had been nearly $8000; even if the dollar should drop to 50 cents, or to the value of the Mexican or silver dollar which has always fascinated the democratic mind, provided American securities don’t depreciate further, I shall still have all that is requisite for keeping up my present way of life: and I could transfer something from my American capitalist income to my London bank-account, if my literary earnings are not enough to replenish the latter. It is probable, therefore, that I shall be able to keep sending you what I send at present, in any case: but the dream of wealth that visited me two or three years ago has vanished.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Five, 1933-1936. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003.

Location of manuscript: Butler Library, Columbia University, New York NY.