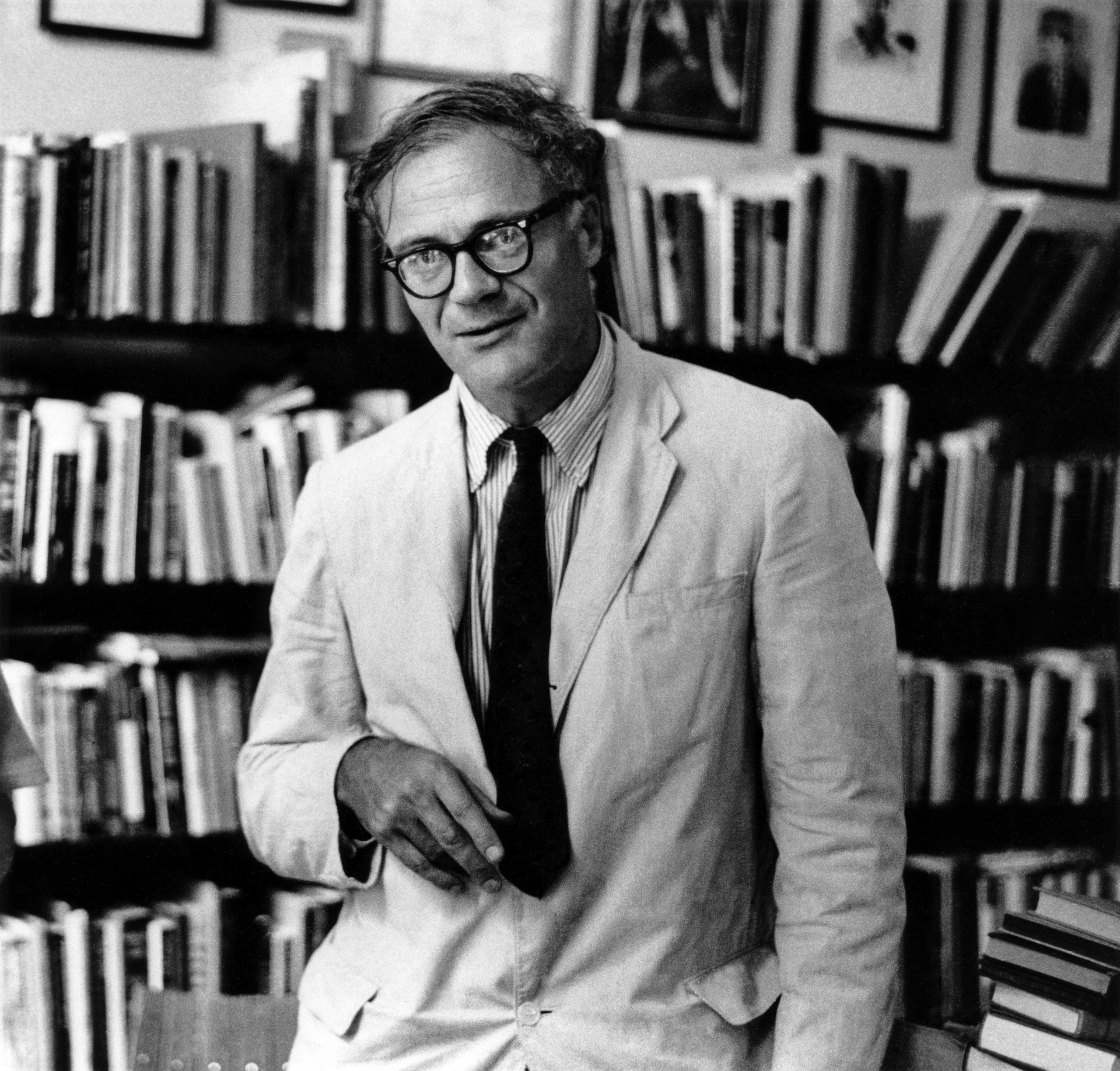

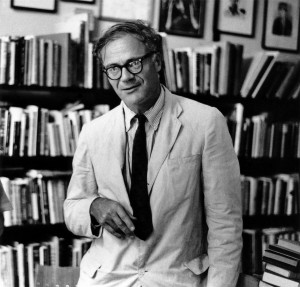

To Robert Traill Spence Lowell Jr.

To Robert Traill Spence Lowell Jr.

Via Santo Stefano Rotondo, 6

Rome. June 24, 1948

Dear Lowell,

Today, to honour la festa della Natività di San Giovanni Battista, your generous box of food has arrived. I am at this moment munching the chocolate, but feel that on the whole you are taking at Washington too tragic and charitable a view of the state of things in Italy, at least in establishments like this of the “Blue Sisters”. We have everything we need to eat, not always (the bread, for instance) of the best quality, but no scarcity of the stock things like butter and sugar. It is true that at my age I don’t ask for much in the way of meat, which is not of good quality always; so that I feel the shortage less than would a normal person. What I feel is the disorder of international policy and the absence of competent leaders in all the nations. But I won’t go into this because my information is not good and I don’t want to antagonize anybody. Let them boil in their own broth.

Is your engagement at Washington coming to an end? What are your plans? And when shall we see more poems? Don’t send me any more boxes but come yourself if you can and want a change of air.

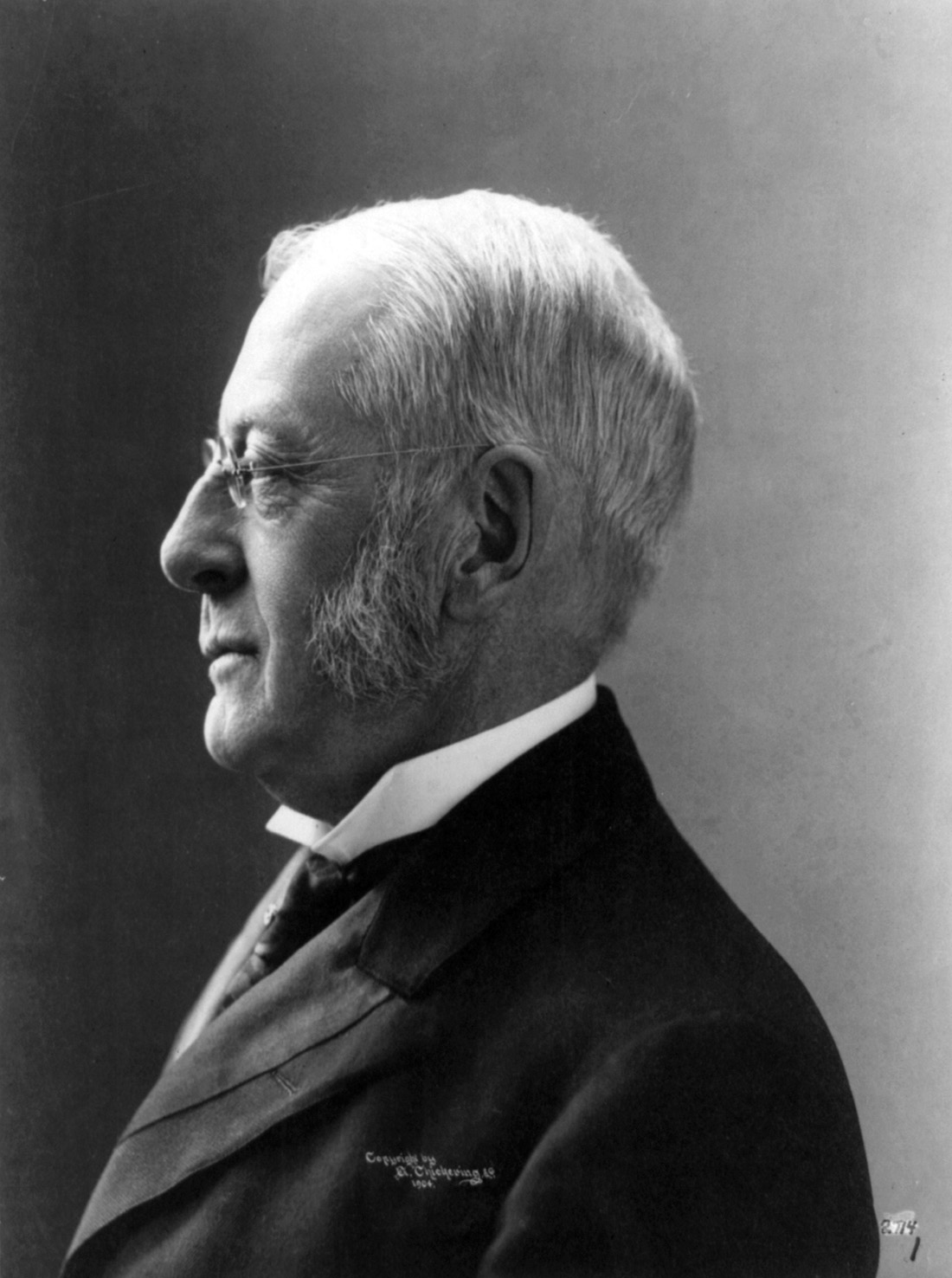

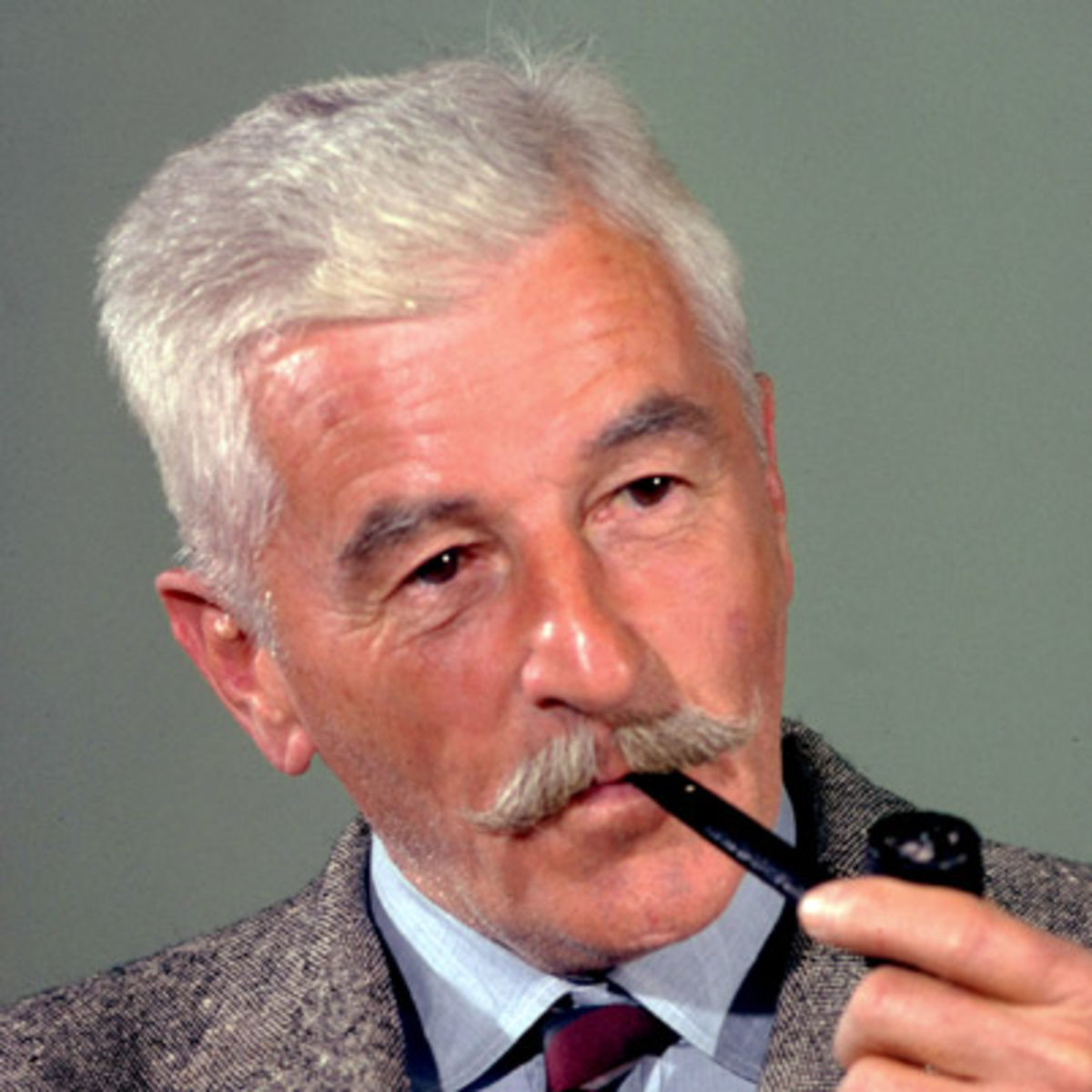

Yours sincerely,

G Santayana

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Eight, 1948-1952. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008.

Location of manuscript: The Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge MA.