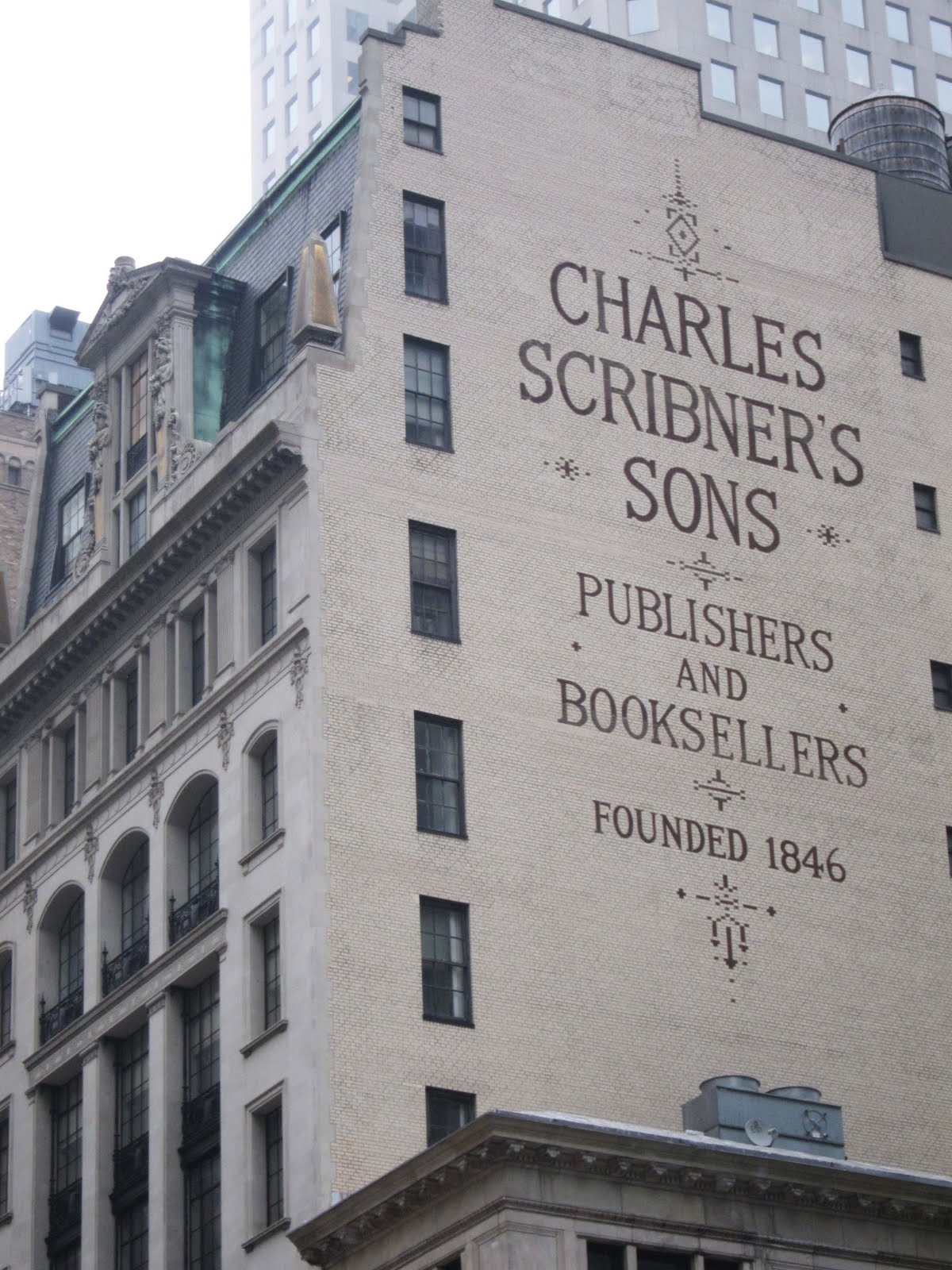

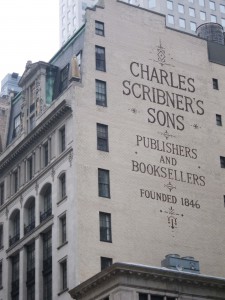

To Charles Scribner’s Sons

To Charles Scribner’s Sons

Cambridge, Massachusetts. June 19, 1904

Gentlemen:

I am much pleased that you find the Life of Reason so promising that you will publish it on the ordinary terms; I had supposed that would hardly be possible, because it will take years, I expect, for the edition to be sold out. However, you are the best judges in such a matter, and I gladly accept your proposition to give me the ten per cent “royalty” I had no desire to intervene in the publication, and much prefer that you should undertake it yourselves, seeing you are disposed to do so.

As to publishing serially, that is of no consequence to me, and any arrangement you think best will suit me. Indeed, in one way, I find the suggestion very convenient, as the revision I am now at work on is taking longer than I expected—the book had grown up in seven years, so that it was full of repetitions and inconsistencies—and I need not send you all the MS at once. The next three books—Reason in Society, Religion, and Art— I will entrust to you before I go abroad; they will be ready, and safer in your keeping, and you can go on with the printing at such intervals as you think suitable. The last book—Reason in Science—I can send to you later, and as it is in many ways the most important it will perhaps do no harm to meditate a little longer on it before giving it a final shape.

I have tried to make the books nearly equal in length, but the attempt has been a failure: the matter could not be pressed, and I hardly wished to expand it. Book II, IV, and V, will be shorter than I, and III (Religion) a little longer. At least, I think so, although I am not good at counting words.

G Santayana

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book One, [1868]-1909. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Libraries, Princeton NJ.