To Rosamond Thomas Bennett Sturgis

To Rosamond Thomas Bennett Sturgis

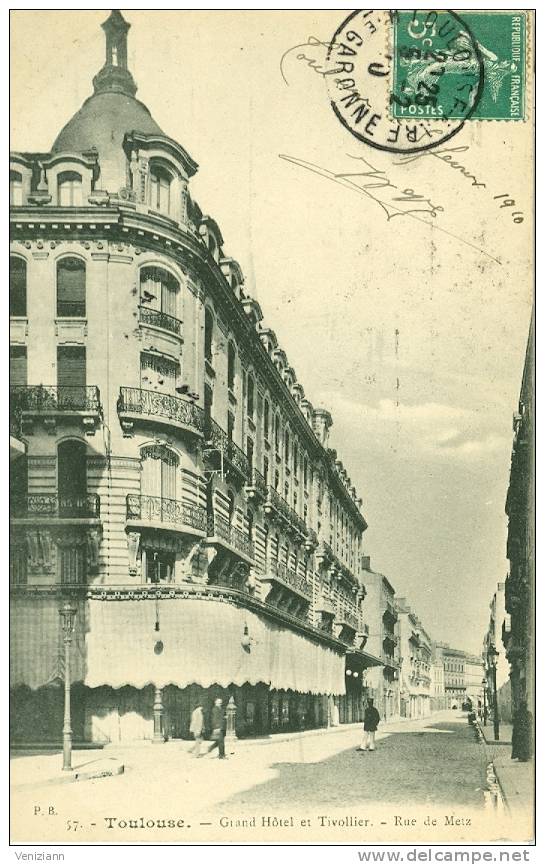

Via Santo Stefano Rotondo 6

Rome, May 3, 1946

Dear Rosamond:

Another box has arrived from you—you are indefatigable—with a jar of apricot jam and a large fruit-cake. In the bottom was a newspaper—the Crimson, I supposed, with Bob’s articles: but no: it looked rather crumpled and the title was The Christian Register. What a disappointment! Perhaps the Crimson will come next time. I don’t understand what it can mean to register Christianity. What Christians are expected to register is their sins, or if they are very old-fashioned, their miracles; and I can’t imagine a Boston publication registering either. Besides, I have been busy of late, in my own way, about Christianity, and I am afraid it has been too much for me at my years, for I have discovered in my book on The Idea of Christ the almost exact repetition on page 247 of three and a half lines from page 244, where they belong. How did this happen? And why didn’t the proof-readers, who included Mr. Wheelock of Scribner’s, Cory, and I, never notice it? Or did they think it was intentional? It was simple witlessness and fatigued attention in my case: it would be a good joke if anyone took it for a burst of eloquence. You know Demosthenes said three things were essential to the orator: repetition, repetition, and repetition. It may be essential to oratory, but it is also found in the talk of old fools.

We have had the much needed rain, and with May summer weather is upon us. I feel well, and encouraged about my book on politics, for which I have invented—ex post facto—a logical arrangement: 4 b/Books or Parts: 1, Preliminaries (which is almost complete), 2, The Generative Order of Society, or The Order of Growth, 3, The Militant Order, and 4, the Rational Order. Under these heads I am going to distribute so much of the stuff, accumulated for thirty years, as seems worth preserving, adding what I have learned since or am learning (from Stalin and Collingwood) that may bring the subject up to date. I don’t expect to live to finish this work, but that doesn’t matter. It will keep me occupied, innocently for the rest of my days.

Yours affly GSantayana

P.S. If you have any photos of yourself or the boys, I should like to have them very much.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Seven, 1941-1947. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2006.

Location of manuscript: The Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge MA

To Curt John Ducasse

To Curt John Ducasse To Paul Arthur Schilpp

To Paul Arthur Schilpp To Henry Ward Abbot

To Henry Ward Abbot To Susan Sturgis de Sastre

To Susan Sturgis de Sastre