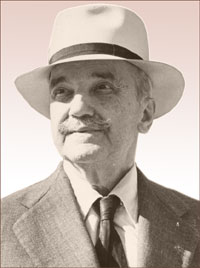

To William Lyon Phelps

To William Lyon Phelps

Hotel Bristol,

Rome. March 16, 1936

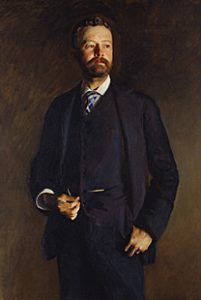

An important element in the tragedy of Oliver (not in his personality, for he was no poet) is drawn from the fate of a whole string of Harvard poets in the 1880’s and 1890’s—Sanborn, Philip Savage, Hugh McCullough, Trumbull Stickney, and Cabot Lodge: also Moody, although he lived a little longer and made some impression, I believe, as a playwright. Now all those friends of mine, Stickney especially, of whom I was very fond, were visibly killed by the lack of air to breathe. People individually were kind and appreciative to them, as they were to me: but the system was deadly, and they hadn’t any alternative tradition (as I had) to fall back upon: and of course, as I believe I said of Oliver in my letter, they hadn’t the strength of a great intellectual hero who can stand alone.

I have been trying to think whether I have ever known any “good” people such as are not to be found in my novel. You will say “There’s me and Anabel: why didn’t you put us into your book, to brighten it up a little?” Ah, you are not novelesque enough: and I can’t remember anybody so terribly good in Dickens except the Cheerybell Brothers, and really, if I had put anyone like that in they would have said I was “vicious”, as they say I am in depicting Mrs. Alden.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Five, 1933-1936. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003.

Location of manuscript: The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven CT.